(Re)Writing unix tools in Rust

Image credit: carbon.now.sh

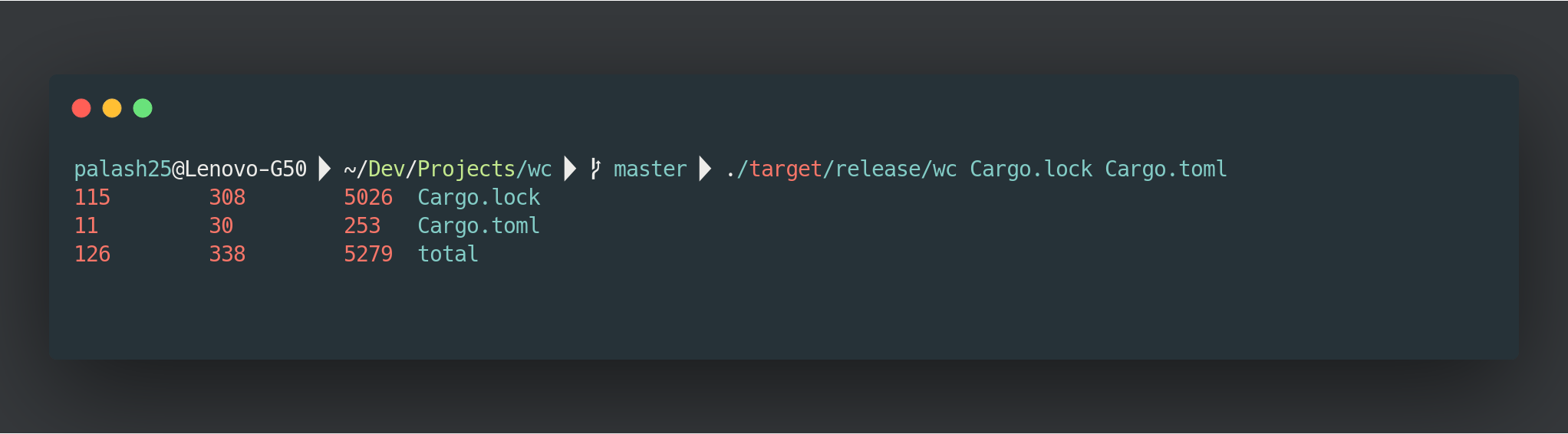

Image credit: carbon.now.shI wanted to learn Rust and was looking for a small and straightforward project to get started with and the wc command in unix caught my eye. Here I will share my experience of writing non-trivial Rust code for the first time.

Target Audience

Newbie rustaceans like myself 😅. Before writing this piece of code I had read some parts of The Rust Programming Language book (which I kept referring to while building this project) and I also worked through the exercises in rustlings (highly recommended)

This post will cover the following:

- Using

structandimplin Rust - Rust style error handling using pattern matching

- Using external crates (in this case

clapandansi_term) - Building and publishing our crate to a registry

- Performance comparison with the original wc (written in C)

Pre-requisites

You need to have the following installed

- Rustup

- Cargo

The Essentials

So we are going to write a port of the wc command. All we need to do read different files, collect some stats about them, print them out and collect a few command-line flags depending on which our output will change. So its essentially a simple File IO program.

Getting Acquainted with cargo

We will use cargo to setup our project, run cargo new wc-rs. If you don't provide any additional flags while creating a cargo project it creates a binary package and you will get this output Created binary (application)wc-rspackage. Alternatively if you want to create a rust library you can pass --lib with the new command and cargo will do the rest. In case of a binary cargo generates the following package structure.

.

├── Cargo.toml

└── src

└── main.rs

Cargo is Rust's official package manager and build tool and comes packed with a lot of features that make Rust development utterly blissful. Never have I ever come across a better package manager while working with other languages.

Cargo.toml holds all of the metadata for our application related to building, publishing and dependencies.

A Quick Script

Ok enough talk lets write some quick dirty code to get started with. In src/main.rs we will write the following code.

use std::env;

use std::fs;

fn main() {

let args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

let contents = fs::read_to_string(&args[args.len()-1]).expect("couldn't read the file");

let lines: Vec<&str> = contents.lines().collect();

let words: Vec<&str> = contents.split_ascii_whitespace().collect();

println!("chars {}\tlines: {}\twords: {}", contents.len(), lines.len(), words.len());

}

This code is written assuming that we only pass one file to our command ./target/debug/wc-rs Cargo.toml as the last argument. We use env crate from the standard library to collect all the command line arguments into a Vec<String>. The first element of the vector being the executable file path and the last being the file name to be read.

Now that we have the args we will try to read the contents of the file. Using the fs crate from stdlib we will open up the file and store its contents into a String using fs::read_to_string. Since fs::read_to_string returns a Result which can have either Ok or Err values we use an expect method to quickly unwrap the Result and panic in case an error is returned.

Now that we have the file contents as string we can get the number of lines, words and characters using the string stored in contents and display them.

We will now build this using cargo build and run our binary using ./target/debug/wc-rs Cargo.toml depending upon the contents of your Cargo.toml you will get an output similar to this

chars 140 lines: 6 words: 23

Some enhancements

We will now add more functionalities like handling multiple files, displaying total stats, command-line flags, etc to make our wc look as identical to the original one as possible. While doing this we will pick up some Rust concepts like structs and impls and familiarize ourselves with using external crates.

We will start with a simplistic approach. Lets save our state (the arguments passed from the command line) in a struct and use std::env to gather the CLI args.

struct Args {

filename: Vec<String>,

flags: Vec<String>,

}

fn get_args() -> Args {

let cmd_args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

let mut args = Args{

filename: Vec::new(),

flags: Vec::new(),

};

// Separate flags from filename

for a in &cmd_args {

if a.starts_with("-") {

args.flags.push(String::from(a));

} else {

args.filename.push(String::from(a));

}

}

args

}

We collect all the CLI args using env::args().collect() into a Vector. Then we instantiate our Args struct and save it to a mutable variable using let mut args. We use mutable because the values of the struct fields will change when we will separte the cmd_args into their respective vectors based on whether they have "-" prefix. The args without a dash prefix are all considered file name(s)/path(s). The last line in the function before the closing brace is an implicit return. Rust will return the last value in a function so you don't have to explicitly mention it by writing return args

Now that we have the CLI args lets move the file handling and line counting logic to its own function.

fn display(file: &String, flags: Vec<String>) -> std::io::Result<()> {

let filename = file.clone();

let mut fobj = fs::File::open(file).expect("couldn't read the file");

let mut contents = String::new();

fobj.read_to_string(&mut contents)?;

let lines: Vec<&str> = contents.lines().collect();

let words: Vec<&str> = contents.split_ascii_whitespace().collect();

println!("{}\t{}\t{}\t{}", lines.len(), words.len(), contents.len(), filename);

Ok(())

}

In our main function we will utilize these two newly written function. We collect the args first, iterate over the all the filenames provided by accessing the filename field of our Args struct.

fn main() {

let args = get_args();

for a in &args.filename {

let res = display(a, args.flags.clone());

match res {

Ok(_) => (),

Err(_) => (),

};

}

}

According to me this is a the most interesting bit of code in our main function

match res {

Ok(_) => (),

Err(_) => (),

};

If you are not familiar with this kind of syntax its called pattern matching. Its a widely concept used in functional programming languages like Erlang, Ocaml, etc. If you go to Rust's wikipedia page and look for the languages that influenced Rust you will find these 3 functional languages: Erlang, Ocaml and StandardML all of which use pattern matching. Take a look at the this chapter of the Rust Programming Language Book to learn more about it.

Fun fact: Before it was self-hosted the Rust compiler was written in Ocaml. 😲

Using external crates

We will be incorporating two crates in our code:

- clap-rs (a )

Aside

Rust is a delightful language with a strict compiler that makes you think about memory management, efficient and feature-complete tools like

rustupandcargo, helpful error messages and a great community. The only downside (even though I don't consider it one) can be slow builds (which is a trade-off if you have a strict compiler like rustc). Since our goal is to learn how to use external crates which will be helpful in our future Rust endeavors we will use them anyway but one should always think twice before adding a dependency to their codebase. Unecessary deps can significantly increase build time which can be an annoyance especially if its a small project like wc. Most things can be done with a